The following sketch was based in part on a much longer article, Twenty Years of CRFG: How We Got There, by C.T. Kennedy, which appeared in the 1988 Yearbook of the California Rare Fruit Growers, pp. 3-17.

California Rare Fruit Growers traces its beginnings to a telephone call received in November 1966 by Paul Thomson in Bonsall, Calif. from John Riley of Santa Clara, Calif. The telephone call led to a meeting at the Thomson home, and later a visit to Thomson’s orchard in Vista, where mangoes, litchis and longans were mature and producing fruit. This led to a realization that among the many gardeners and orchardists along the subtropical Pacific Coast there was a store of knowledge and experiences which might help them all in the cultivation of rare fruits.

The CRFG did not happen overnight, however. Thomson canvassed his friends and acquaintances and corresponded regularly with Riley. By November 1968, there was enough interest to form a group. A name was chosen to best express their objective: the California Rare Fruit Growers. Thomson and Riley drew a manifesto and 27 others joined the group as charter members. One thing was certain: the need for a timely publication through which members could exchange knowledge. In these early years the focus of CRFG was almost exclusively on California conditions. A list was drawn up of all the unusual fruits known to the founders at that time, along with a membership roster. The fruit list was a puny thing compared to the one we know now, and serves to remind us just how far we have come. The old list of fruits “not known in current cultivation” is now obsolete, and the hardiness of many fruits can be adjusted several degrees downward. Early on CRFG made discoveries that today seem a bit quaint: that mangoes felt at home in Coachella Valley, for instance, or that white sapotes and feijoas can be fruited in most areas of the state–indeed, the northern limits of their culture is still unknown. CRFG still has work of this sort to do and a purpose to serve in California and elsewhere. CRFG members have not distinguished a boundary between the possible and impossible in horticulture, and have made fruit growing immensely more interesting than it was in the days of pomology manuals and all-knowing county agents.

John Riley edited the Yearbook and Paul Thomson produced the Newsletter in his home. Thomson handled the paperwork and Riley began the seed fund to obtain and distribute seeds of new fruits. CRFG held its first general membership meeting in Bonsall, the start of the CRFG effort to provide field trips, demonstrations and social events to expand members’ activity beyond the mailbox and armchair. CRFG members from the beginning have included commercial fruit growers, academicians, researchers, nurserymen, county agents, and of course the core of backyard fruit growers. CRFG grew to 379 members in 1971 and 595 in 1975. This involved just too much work for one or two persons, and in November 1978 the CRFG membership voted to draw up a formal Board of Directors, a 13-member governing body that selects a president and other officers and manages the affairs of CRFG. Later the organization completed its incorporation.

Because of the broad range of climates within California, and possibilities for growing different fruits from north to south, CRFG considers rare fruits to include the unusual and unappreciated, fruits difficult to grow by reason of climate along with extraordinary and superior forms of conventional, temperate zone fruits. Our field of interest has been further enlarged to include unusual vegetables, cereals and seasoning plants–the other rare edibles from the vegetable kingdom. To give better scope to our members’ interests, and opportunity to share experiences, geographical chapters have been formed. Each chapter has regular meeting programs, which generally include pictorial presentations, fruit exhibits and tastings, skills demonstrations, field trips, plant and supplies sales, raffles, etc. Chapters operate with considerable independence from CRFG, have their treasury and officers, and collect their own fees to cover the cost of newsletters and activities. Today there are 16 California chapters with one each in Arizona and Texas.

The chapters undertake informally to bring rare fruits to public notice in a variety of ways. These include such diverse activities as assisting in creation of certified farmers’ markets, connecting rare fruit marketers with member growers, and providing plant sales to encourage backyard nurserymen to propagate unusual fruit plants. Several chapters have circulating and other libraries. Some chapters maintain demonstration fruit plantings in public arboreta or sponsor experimental orchard plantings. Some chapters hold annual scion exchanges. The ones sponsored by northern chapters each winter are collectively widely noted for the many hundreds of fruit cultivars available. Most southern chapters produce exhibits for county fairs–frequently receiving best-in-show awards.

An important aspect of CRFG activity from the very start has been the publication of some kind of official journal, although the form has evolved over time. In the beginning the format was a quarterly Newsletter (later renamed The Fruit Gardener) containing articles of timely interest and an annual Yearbook or Journal of topical articles. In 1990 a major advancement occurred when the various pieces were reconstituted into an enlarged bimonthly publication, THE FRUIT GARDENER. This took on the look of a proper magazine, 8-1/2 x 11″ in size and using color in its covers as well as occasional inside color photography, plus a crisp new font and better organization. Refinements in the meantime include more internal color and a tighter publishing schedule. Efforts have also been made to broaden the appeal with new special departments and more articles from and appropriate to an increasing range of members outside California.

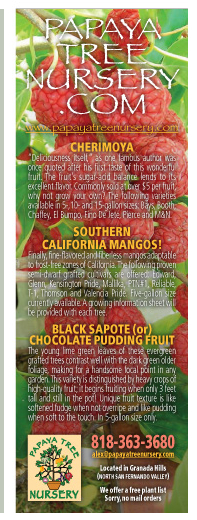

The establishment our web site (https://crfg.org/) in mid-1995 was another major advancement with implications that are still unfolding. The award-winning site today is a powerful online file of fruit-related information–all of which is free for the taking. Components of the site include all of the earlier Fruit Facts plus an equal number of new Fruit Facts, the 20-year Index of CRFG Publications (with descriptions of 250 rare and unusual edible plants), the Fruit List, the list of CRFG Member Nurseries and Fruit Sources, reprints of significant articles from earlier CRFG publications and much more. Another important facet of our web site is a “Contact Us” page that visitors can use to post questions or seek additional information.

A major benefit of our Internet presence has been the addition of a significant number of new members. Today CRFG membership stands at 3,100+ and is growing for the first time in a decade. A majority of these new members are from outside California, which adds a certain richness to the organization and strengthens our position as a truly international organization.